There may be an alternative to mandatory vaccines and the inherent privacy and security concerns of either paper or electronic vaccine passports: allow people to opt out, but normalize the use of masks in densely populated, public, indoor settings when conditions suggest caution is demanded.

In the United States, this requirement should be tied directly to CDC reported rates of dangerous, communicable diseases with wastewater surveillance informing decisions. Medical research should be funded to track the effectiveness of masks against flu and anything else that’s feasible, not just COVID-19.

Ongoing investigation of the role aerosols—and inadequate ventilation—play in spreading common diseases demands equal attention and funding.

I, for one, would not return to an office as of May 2021 without a mask on my face if the space didn’t promise four to six air changes every hour or a fully vaccinated cohort of coworkers! This Wired story is a must read for those who’d like to understand the origins of medicine’s deeply flawed 5 μ myth defining “airborne” pathogens.

While our coronavirus memories are fresh, we owe it to future generations to prepare better for the next global outbreak. It is as inevitable as SARS-CoV-2 was. Fumbling our collective response, however, is not preordained.

We’ve learned a lot during the course of the coronavirus pandemic.

Ample real world evidence is now available suggesting that even simple homemade cloth coverings reduce the risk of infection from at least this one airborne virus. Flu also virtually disappeared‡ during the 2020-21 season, though that could be as readily attributed to social distance and isolation as opposed to masks.

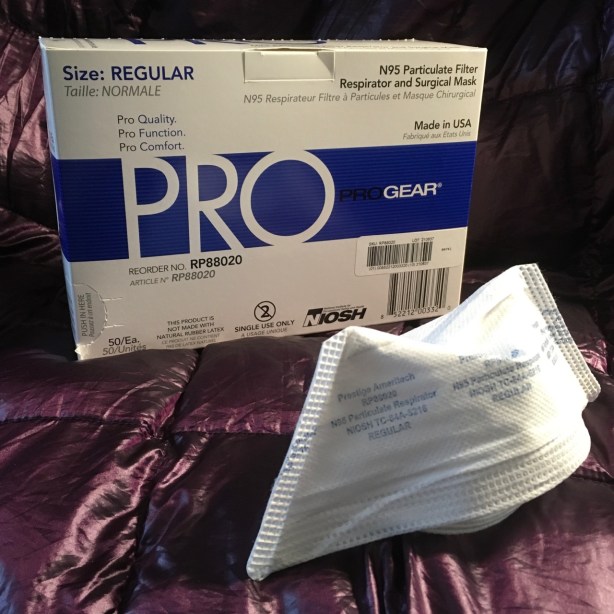

In the absence of the worldwide supply chain disruptions common early in this pandemic, more definitively effective surgical and N95 masks are easily obtained and affordable. Employers with public storefronts should have boxes of them deployed in the workplace in the same way food service companies provide gloves to their workers.

As with gloves and hairnets in restaurant kitchens, masks should be the immediate, hygienic response to entering the personal space of unknown persons with unknown vaccination status while any community is in the throes of an infectious agent.

Massachusetts’s governor is quoted in a May 7th Boston Globe opinion piece as saying, “some people have ‘very legitimate reasons to be nervous about a government-run program that’s going to put a shot in their arm.’” The same piece goes on to report, “Attorney General Maura Healey… this week repeated her call for public employees to be vaccinated as a condition of their jobs.”

Requiring every public employee in a customer facing position to wear a face mask at work unless s/he chooses to offer verifiable proof of vaccination seems like a cheap, simple, practical solution to me. As every scientifically literate, law-abiding citizen of the United States now knows, wearing a mask is no more difficult* than wearing pants.

Rome, the power house of the ancient world, believed trousers were ridiculous, barbaric garments. Quite literally, Romans, like the Greeks before them, saw pants as uncivilized clothing fit only for uncouth Goths and Vandals. The entire Western world, and most people around the globe, now don trousers without compunction. Masking one’s face requires no greater degree of adaptation!

Most of us could decide which we prefer at work: to wear a mask, or to accept vaccination. Crucially, the public at large ends up protected either way.

I think it is likely that I, personally, will never want to fly again without a face covering, if only because I’m so well aware of my own tendency to touch my face and even bite my nails when experiencing anxiety. It’s a terrible habit I’ve never been able to break, but a comfortable face shield or mask would remove almost all of that risk to my health.

There will always be liars and attempted cheats, of course. Responses to those caught committing public health fraud should be proportionate and focused on preventing harm to the community.

Perhaps being fitted with a device designed like the ankle bracelets employed for house arrest for a period of time would work, offering a visible warning to strangers while broadcasting via Bluetooth? a message alerting those in the vicinity of the need to increase social distance. This could be a system that works with individual’s cell phones, or a device required for public occupancy of spaces meeting certain size or density limits rather like the requirement to install smoke alarms and fire sprinklers before opening a hotel or nightclub for business.

The primary solution is to normalize the continued use of masks in dense situations where we crowd together with unknown persons. The secondary need is for public spaces to meet reasonable, updated standards for safety in light of our current understanding of risk in the post-COVID-19 world.

Once COVID-19 vaccines are fully approved by the FDA, I do believe that employees who work specifically with the most vulnerable population should be required to accept vaccination or leave∞ those particular roles.

Aides in nursing homes should not be able to opt out of coronavirus vaccines, nor the flu vaccine in normal years, nor should nurses serving the immune-compromised. Prison guards—who work with populations literally unable to escape from unvaccinated sources of exposure—are another obvious group whose personal choices should not be allowed to endanger the lives or health of others.

The actual conditions of employment for such positions demand a workforce that doesn’t subject other people to unnecessary risk so easily mitigated by inoculation. Case in point: the unvaccinated Kentucky health care worker who caused the death of three elderly residents of the nursing home where s/he worked. To pretend otherwise makes a mockery of both human decency and common sense.

In another example: a recent study published in JAMA showed that 46% of organ transplant patients produced zero antibodies after a complete 2 shot course of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. It’s unreasonable that such individuals should be unknowingly subjected to the ministrations—however well-intentioned—of unvaccinated health care workers, certainly not without the immune-compromised patient’s being informed of their relative risk and given the opportunity to offer fully informed consent to taking said risk.

Face masks could also offer an effective solution for the conflict between public school vaccination requirements and anti-vaxxer parents currently allowed in some states to claim religious or other non-medical exemptions for their children.

Further research might prove that masks are not effective against every disease against which we have mandatory childhood vaccinations, but face coverings could potentially eliminate the friction between parent choice† and community health in the context of the vital public good which is free, universal education.

Where freedom is the prize—and outbreaks of vaccine-preventable childhood infectious disease remain rare in America—I’d argue that the value of face masks as an alternative to mandatory injections is well worth exploring.

Western medical science was patently wrong, before COVID-19, when it declaimed that face coverings offered no protection from infectious disease. We still aren’t sure if they protect the wearer so much as those in the vicinity of a masked, sick individual, but we do have substantial evidence that widespread adoption of masks can protect populations during a deadly outbreak.

Perhaps most importantly, where even the most well-vetted, safest vaccine or medication carries some tiny risk of harm to its recipient, wearing an appropriate, well-fitting mask correctly has virtually zero chance of injuring anyone. Low cost interventions with few side effects are ideal public health measures.

Asian nations which had internalized the historical lessons of earlier epidemics had it right; many** normalized face coverings during flu season. Now we know better, too. Science proves its inherent value when we incorporate new data into our body of knowledge, especially when we recognize data challenging existing beliefs and ingrained patterns of behavior.

This BMJ editorial (PDF) highlights the danger of clinging to false understandings. This opinion piece by Dr. Zeynep Tufekci is well worth a read on the subject of organizations lurching only slowly toward acceptance of new information challenging medical and scientific preconceptions.

Before the next pandemic, we should take great pains to study when, where, and how cheap, medically risk-free facial coverings work to effectively control the spread of disease. How many thousands fewer would have died if we’d deployed masks as a solution worldwide in days instead of months in 2020?

This is not merely a political issue. It is a matter of public health. Where solutions exist that preserve both life and liberty, we owe it to democracy—and humanity—to explore every possible compromise.

♦

‡ Per the CDC, roughly 1000 flu cases were diagnosed during the pandemic 2020-21 season vs. more than 65,000 cases in the more typical 2019-20 season.

* As with trousers, some are the wrong size, and some are more comfortable on a particular body than others. Trial and error may be required to find the perfect fit for a given individual. Compared with the effort necessary to remediate infecting a susceptible individual with a life-threatening disease, this process is, at worst, a trivial inconvenience.

∞ Per the Boston Globe: One of the major senior care operators in the state of Massachusetts came to a similar conclusion before COVID-19, though the quote perversely suggests that the organization was more interested in shaming staff members as opposed to protecting elderly residents:

“A year before the pandemic, Hebrew SeniorLife required flu shots for the first time for staff. Administrators achieved 100 percent compliance by imposing what seemed at the time an onerous condition: Holdouts would be required to wear masks 24/7 during flu season.

‘That was totally embarrassing then, but not now,” Woolf said. “We don’t have that hammer anymore.’”

In my opinion, after legitimate scientific studies were conducted to confirm that mask use by unvaccinated staff protects vulnerable patients to an equivalent level as vaccinated staff with faces uncovered, this could be a sufficient and highly appropriate alternative to mandatory shots in some cases.

† Voluntary residential situations for children under age 18 should probably be held to a higher standard, in my opinion, and strictly require vaccinations for all but medically exempt participants. Absent direct parental supervision, it seems unreasonable to subject anyone else’s child to unnecessary risk due to personal choices that contradict the best current medical advice.

** Routine wearing of masks was imported to Japan from Western nations who’d adopted them as one response to the influenza pandemic of 1918-19. Unlike we Americans, Japanese culture never dropped them as a reasonable personal response to being contagious after the urgency of the Great Influenza subsided.

This Huffington Post article suggests that the Chinese adopted protective face coverings even earlier: “In 1910 and 1911, citizens were encouraged to wear masks to combat the pneumonic plague outbreak in Manchuria.”

The article goes on to point out that other Asian nations picked up the habit of covering faces during outbreaks due specifically to the SARS epidemic of 2002-2003. I’ve read that Koreans, in particular, actually viewed masks in a somewhat negative light as a foreign, Japanese import before the first SARS crisis.

‡ One reason I’ve avoided working in food service—since a mandatory stint in my college dining hall as part of my financial aid package—or in health care is that those products are actually essential for life. The stakes, therefore, can be sky high, potentially justifying extreme behavior on the part of the guest. I’m unaware of anyone every dying due to a lack of professional brand shampoo.

‡ One reason I’ve avoided working in food service—since a mandatory stint in my college dining hall as part of my financial aid package—or in health care is that those products are actually essential for life. The stakes, therefore, can be sky high, potentially justifying extreme behavior on the part of the guest. I’m unaware of anyone every dying due to a lack of professional brand shampoo.