I’ve noticed that I often bring up in conversation one or more of the fascinating books I’ve been reading lately, only to fail utterly at recalling titles or authors’ names. I’ll take this opportunity to at least make a handy reference available for anyone who cares to follow up on something I’ve said.

Just check my blog!

Non-Fiction

Autobiography of Janet Frame, To the Is-land (Volume 1) and An Angel at My Table (Volume 2)

Anathema!: Medieval Scribes and the History of Book Curses by Drogin, Marc

Nine Nasty Words: English in the Gutter: Then, Now, and Forever by McWhorter, John

On Tyranny Graphic Edition: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century by Snyder, Timothy

Fiction

Young Adult

Black Enough: Stories of Being Young & Black in America edited by Zoboi, Ibi

Horten’s Miraculous Mechanisms: Magic, Mystery, and a Very Strange Adventure by Evans, Lissa

New Kid by Craft, Jerry

Mystery/Thriller

The Crossing Places (Ruth Galloway #1) by Griffiths, Elly

Maisie Dobbs mysteries The American Agent (#15) and To Die But Once (#14) by

Thrice the Brinded Cat Hath Mew’d (Flavia De Luce #8) by Bradley, Alan

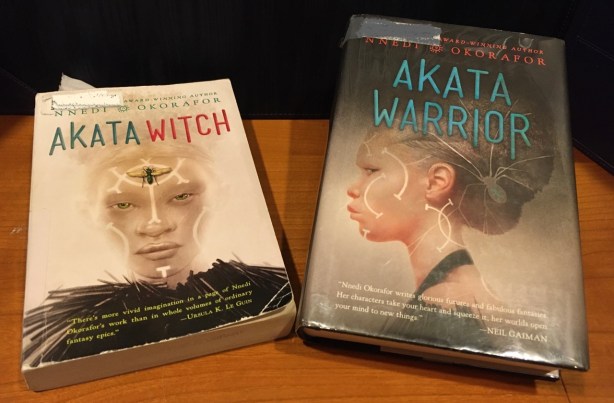

Fantasy

A Darker Shade of Magic by Schwab, V.E.

Reading Notes:

Making democracy great again: modern tyranny & WWII’s British endurance of the Blitz

Pardon me while I tie together my candy floss consumption of mystery novels (here, two of the more recent titles in the Maisie Dobbs series) with Snyder‘s On Tyranny. Ms. Winspear, Dobbs’ creator, has shepherded this particular character from the period just after The Great War to World War II and the Blitz. Invasions and bombings in the 1940’s segue tragically well to a slim, topical volume about tyranny released in 2021.

On Tyranny is the first “graphic novel” I’ve read that isn’t… um… a novel. I’d say “graphic non-fiction” would be a better if unwieldy label. These “twenty lessons from the Twentieth Century” present as a collection of illustrated brief essays.

There’s a whiff of Eric Hoffer‘s The True Believer to it.

Artist Nora Krug absolutely enhances Snyder’s message with her colorful yet slightly creepy† style. I find such illustrations particularly haunting when a child-like medium communicates such portentous messages.

Immersing myself in the fictional experience of Maisie Dobbs enduring the Blitz somehow prepared the fallow field of my mind for open conflict in Europe and the new Cold War dawning along with 2022. Perhaps oddly, I’m made hopeful by the reminder that our grandparents fought similar enemies—and won—in an earlier generation. This awareness sharpens my passion to work against fascism in every way I personally can.

The Maisie Dobbs stories—The American Agent in particular—draw in sharp relief that period when Great Britain stood alone against a fierce onslaught of illiberal governments on the continent. Personal sacrifices by individual English people were many, and the costs were high. It’s easy to forget that “America First” was a slogan used then by U.S. citizens who preferred to let the U.K. sink or swim under Hitler’s assaults alone.

Much of On Tyranny is difficult and distressing to read, but the author’s fundamental argument is against defeatist resignation and capitulation to lassitude. Snyder’s point is that we all must do our bit as citizens if we want to enjoy life in a free, democratic society.

I’m glad I requested this volume from the library when I did, because it was there on my shelf as my news feed filled with oligarchical Russian aggression against Ukrainian democracy.

I Buy Banned Books

Another graphic work I read this month—this one is actually a graphic novel!—was Jerry Craft’s New Kid. My thanks to the reactionary racist snowflake parents in Texas who tried to get it banned: I enjoyed it a lot. Any kid struggling to fit in as “the new kid” will identify with this protagonist. It would be the perfect gift for an artsy kid moving to a new neighborhood or school.

While I disagree totally with those who would ban Maus‡ for children old enough to handle content as tough as genocide, I can at least understand why a depiction of nudity or inclusion of a few bad words frightens school board members in rural America.

With New Kid, however? Frankly, unless you object to the very existence of brown people experiencing their own feelings in white spaces, there is nothing ban-worthy in the book. It does not, in any way, shape, or form, teach Critical Race Theory as some parent claimed in an article I read; CRT is never mentioned in the book, which mostly covers typical young teen “fitting in” anxieties at a new school.

New Kid does address how characters from different backgrounds respond to being a minority in a setting with a clear majority, it just does so by telling a normal kid’s story in a perfectly realistic way.

No conceptual legal framework required.

That book you can’t recall the title of…

Now I have to mention Horten’s Miraculous Mechanisms. This is a bit of a younger kid’s book than most of the Young Adult stuff I’ve read lately. Why? Because it is a book my older teen read many years ago, then misplaced in our messy house, then couldn’t ever find again. He kept looking for it, though.

“What’s the name of that book…?”

It became one of his, “What’s the name of that book…?” novels.

Horten’s Miraculous Mechanisms turned up way at the back of the bottom drawer of the younger sibling’s desk. Said sibling has never read the book so has perhaps just been hiding it like a wee punk these past few years. The desk in question was a mess of mighty proportions that got cleaned out during February school vacation week.

I’m glad to know I’m not the only one who does this “What’s the name of that book…?” thing. I’m a little sad that I’ve passed on my tendency to the habit to my eldest child.

Our best shared family example of this: The Valley of Secrets by Charmaine Hussey. My kid and I both found this story wildly unique and unforgettable, but neither author nor title sticks with us the way the moody atmosphere and lush descriptions did. We could both also ID it on the shelf by its distinctive leafy cover. Valley of Secrets will be appreciated by readers who relish a well-drawn world who can tolerate a slower pace to the “action” plot.

Horten’s Miraculous Mechanisms is not, as my teen will tell you, “that Hugo Cabret book.”

The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick is the one about the kid living in the walls of the Paris train station. When my teen searched for Horten’s Miraculous Mechanisms, people kept telling him he must be looking for Hugo Cabret.

There are, in fact, miraculous mechanisms—or, at least, magical ones—in this book about Horten, but, unlike Hugo, Horten himself is not the tinkerer-in-chief. Horten is a fairly average kid, kind of annoyed by his parents, and short for his age. He does move to a new to him town, discover an interesting family legacy that includes a bit of a treasure hunt, and meet new people. Some of those folks turn out to be friends, and others, foes.

Most of the magic in the novel is of the stage magician variety, but the story does dip into more mystical waters by the end.

Horten’s Miraculous Mechanisms was a quick read for adult me, but I enjoyed it, devouring it in a single sitting on a snowy afternoon, and I’d say it scores relatively high on the freshness scale. It did not feel like all the other child–has-adventure novels I’ve read.

Anathema ain’t what it used to be

Finally, allow me to end with the delightfully specific Anathema!, a semi-scholarly history of the curses often penned into hand-written books by medieval scribes. Though seriously researched, I’d describe this book as more for fun than academic in tone. It’s also printed in an unusual short/wide format that made it feel rather special to read.

Finally, allow me to end with the delightfully specific Anathema!, a semi-scholarly history of the curses often penned into hand-written books by medieval scribes. Though seriously researched, I’d describe this book as more for fun than academic in tone. It’s also printed in an unusual short/wide format that made it feel rather special to read.

Crafting a book entirely by hand was a heck of a lot of work, of course, so the threat of excommunication—literal anathema—was deemed a reasonable one against any who might dare to deface or steal a precious tome inked by a scrivener.

Interestingly, book curses continued to be included in early printed volumes as well, even after the printing press made production somewhat less tedious.

Perhaps my favorite thing about Anathema! is its concluding observation that the librarian no longer has quite so much to hold over the head of his or her wayward reader now that the average person doesn’t literally fear the fires of hell.

Drogin ends the book with these lovely lines:

“Where once echoed the fury of God now lies an insipid whimper:

A fine of 5¢ per day will be charged…”

♦

†Can I call Krug’s work “Beavis & Butthead in the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine” without giving a negative impression? I’d advise you to read the graphic edition of On Tyranny—or peruse the illustrator’s website—to judge for yourself if you’re baffled by my attempt to use my words to describe her pictures.

‡Art Spiegelman’s Maus is a multi-volume memoir that depicts the experiences of the author’s own family during the Holocaust. Spiegelman draws Jews as cartoon mice, Nazis as cats, Polish people as pigs, and Americans as dogs in the work. A school district in Tennessee removed the book from its eighth grade history curriculum purportedly due to one instance of cartoon “female nudity” and a handful of curse words.

The nudity in question is a top-down view of bare breasts on a woman dead in a bathtub. It cannot by any stretch be viewed as erotic. The rough language in Maus doesn’t hold a candle to the obscenity which was Nazi behavior during the Holocaust.

I own a two volume, boxed Pantheon set of Maus I & II printed in 1986. My kid who home schools has Maus on his reading list.

I’m grateful to the skilled teacher,

I’m grateful to the skilled teacher,