This isn’t medical advice. I’m not qualified* to offer that.

I am simply a self-educated consumer who lives with a chronic health condition. I’ve drawn my own conclusions from research done as an intelligent lay person, tempering it with common sense. I invite you to do the same.

I am simply a self-educated consumer who lives with a chronic health condition. I’ve drawn my own conclusions from research done as an intelligent lay person, tempering it with common sense. I invite you to do the same.

Many of us diagnosed with autoimmune conditions, degenerative neurological diseases, and chronic pain will be prescribed antidepressants. There are fine reasons for this.

Some chronic pain responds positively to antidepressant medications. Given in lower doses than those prescribed for psychological reasons, side effects† are often less as well.

Here’s a link to a (long, almost 2 hrs!) YouTube presentation by Dr. Dan Clauw, M.D. that offers a great explanation for the current understanding of why these drugs may help certain types of pain.

Depression is also a normal human response to learning you can expect to spend the rest of your life with constant pain or in a rapidly degenerating physical condition.

That is a depressing situation for any rational person to contemplate. Treating mental health problems is important, and I do not sit in judgement of anyone who takes pharmacological steps toward better self care.

If you are a danger to yourself, please seek immediate, aggressive care. Do whatever it takes to get well. Your life matters.

That said, I’ve recently learned that the major physical symptoms of depression mirror almost exactly those of a vitamin B-12 deficiency. Hmm…

Even patients with valid diagnoses of other conditions—here’s a study about multiple sclerosis, for example—often have other stuff going on in the body that can make symptoms worse. Large numbers‡ of hospitalized, depressed patients have measurable Vitamin B-12 deficiencies.

It isn’t known yet whether B vitamin deficiencies help create conditions that allow us to develop disease, result from lifestyle responses to living with chronic illness, or are direct side effects/symptoms of disease processes.

I’d argue that the underlying mechanism doesn’t matter so much when we’re talking about supplementing with vitamin B-12.

Why? There is no known upper tolerable limit for safety for supplemental B-12. Say that in plain English? No one ever “overdosed” on this vitamin.

Here’s a link to a more reputable (than me) resource, a state university, for detailed mainstream medical information on the subject of Vitamin B-12. And another to a US government fact sheet on the vitamin for American consumers.

B-12 is water soluble. If you take too much to be used by your body, it will leave your system naturally via your urine. You might “waste” the vitamins you’ve bought and paid for, but odds are tiny** that they will hurt you in any appreciable way.

If someone is ready to prescribe antidepressants to a patient, that patient must have at least one medical doctor who could also be consulted about taking vitamin supplements. Ask your doctor before starting a new treatment, including Vitamin B-12, but, odds are, you will be told this is safe to try.

You may also hear that vitamin B-12 won’t help you. But, then again, antidepressants aren’t a guarantee either. They include a long list of side effects, some of which are very unpleasant. Those prescription pills can also be expensive.

Also, it’s just as unscientific to assume the vitamins won’t help you as to assume that they will.

I’ve come to realize that no one cares as much about my health outcomes as I myself do. With good insurance and caring doctors, I’m still left with unanswered questions and a merely tentative diagnosis for what causes my chronic pain and fatigue. Where stakes are low and scientific certainty is lacking, I choose to perform nutritional experiments upon myself.

If it is highly unlikely to hurt you, and it could help you, why not take some extra vitamins for a while and see if you feel better, too?

Assuming your doctor said such a trial is safe, the only possible barrier is cost.

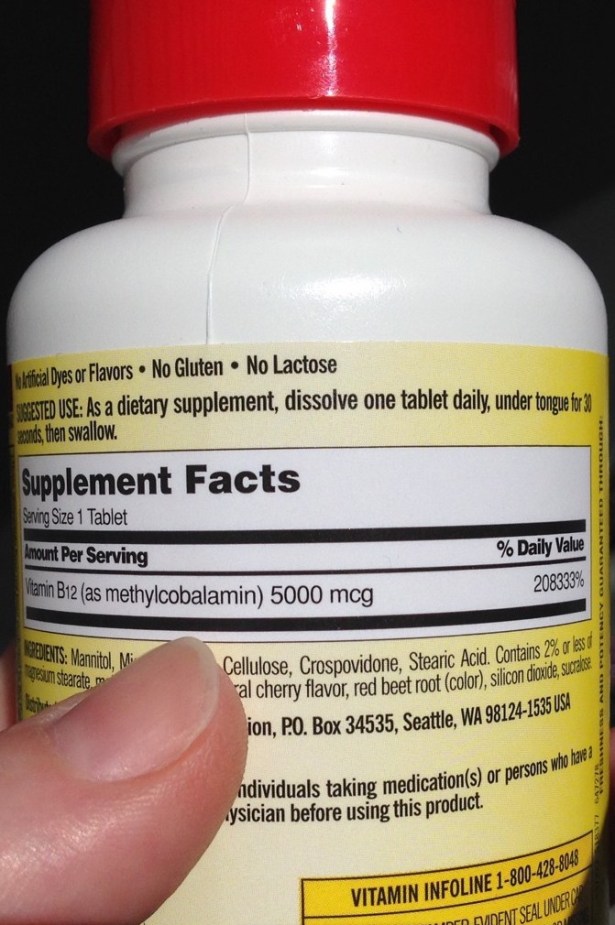

I picked up a bottle of store brand vitamin B-12 at wholesale giant Costco with 300 pills for $19. Each offered thousands of percent (20,833%) of the RDA***, making a bottle good for the better part of a year taking one per day.

That works out to $23.12 annually. Costco typically offers very good value.

At an expensive local vitamin specialty retailer, a three month supply (of 16,667% RDA pills) cost $16, coming out to about $64 per year. I suspect it would be hard to spend much more than this for these vitamins.

There are several forms of B-12 available, and both of these offerings are for the most expensive type, Methylcobalamin.

There are several forms of B-12 available, and both of these offerings are for the most expensive type, Methylcobalamin.

Some users have reported that the most common, cheaper form, Cyanocobalamin, doesn’t resolve their symptoms, but the Methylcobalamin form does. At less than $20 per bottle, it seems within financial reach of most Americans to do this self experiment with the potentially most effective version of the supplement.

My two sample bottles also both contain dissolving lozenges to be held under the tongue rather than swallowed and processed through the digestive system. Again, some argue that a sublingual or injected B-12 is more effective than a swallowed dose. I went out of my way to test this type of supplement, just in case, though science tends to think it is irrelevant for most.

In all of this, note that my primary interest is in clinical results, i.e., how I feel. It will be great if research comes to understand why and how B-12 or any other supplement improves patient outcomes. But I am not a working scientist.

The bottom line for how I make a decision about self-treatment comes down to whether or not I feel better, and at what risk.

The “clinically small” improvement of a group of MS study participants quoted above may be of only slight statistical significance, but when your function or your sense of well being has descended to, say, 25% of your old normal, well, then, 27% or 30% represents a win.

I don’t know what you should do to help yourself live a healthier life. I do have some opinions about which alternative health practices represent good risks worth a try for a person in pain. Perhaps this little experiment can ease some of yours, too.

Your body; your choices. Make them in good health.

♦

*My education in both Biology and Chemistry ended in high school as my college science classes were limited to Physics courses. My major was Mathematical & Physical Sciences with a concentration in Computer Science.

†Make no mistake that the side effects can be significant, however. They are also likely to affect your offspring, not just yourself. There are studies showing this in very obvious and less direct ways.

Powerful drugs are appropriate to treat significant illness, but I’d argue that they should be employed after milder alternatives have been tried and found insufficient.

‡Other sources, regarding. depression.and .neurological and psychiatric disorders

**There are some instances of allergic reactions to vitamin B-12, but I only read of such response to injections (shots), not over the counter vitamin pills. Reports of acne or skin rash in response to large dose vitamin pills do occur with some regularity.

You decide whether temporary skin issues are something that would stop you trying a larger dose of this vitamin for yourself.

***In most cases, we do NOT know the “optimal” level of vitamin intake. Vitamin B-12 reference ranges vary from 180-914 ng/L in the USA, 135-650 pmol/L (183-881 pg/mL) in Australia, and 500 – 1300 pg/mL. (ng/L=pg/mL, so no conversion necessary there.)

If you think this is an important thing for people to know, write to your government representatives and tell them you support basic nutrition research. Private companies have very little motivation to pay for this kind of work; there’s no resulting drug patent to fund the endeavor.

There’s a reason some public services, like infrastructure and basic research, are paid for by taxation. Otherwise, they simply aren’t available to all of us.